Greece 2016: Apathy, Anger, Historic Outrage and the Molotov cocktail hour

As regular readers will know, our examination of values and their cultural impact has been mainly focused on the UK – the home of our research and data. This is about to change.

Over the past four years we have extended our research into over 20 countries comprising over 60% of the world’s population - and now have values data. In an ever more globalised world, this is exciting – and if you or your organisation have a particular need for such data, please get in touch.

Over time we will publish some of our non-UK data, but usually as a comment on a specific piece of media where we feel our analysis can help understanding.

To begin this series, we watched the first part of the two part BBC 2 documentary ‘Greece with Simon Reeves' and recommend you do so before reading further. (Sadly, we cannot control availability so please accept our apologies if it is no longer available).

A range of very important takeaways from the documentary are:-

- The stoicism of people on the Aegean Islands;

- The historical perspective of people on Crete and their connection with the past;

- The organized ‘ritualized’ anger that occurs almost daily on the streets of Athens.

These behaviours and attitudes are all a reflection of the values of Greece – and, in particular, the unrelenting societal turmoil of the last 60 years in general, and the last 15 in particular.

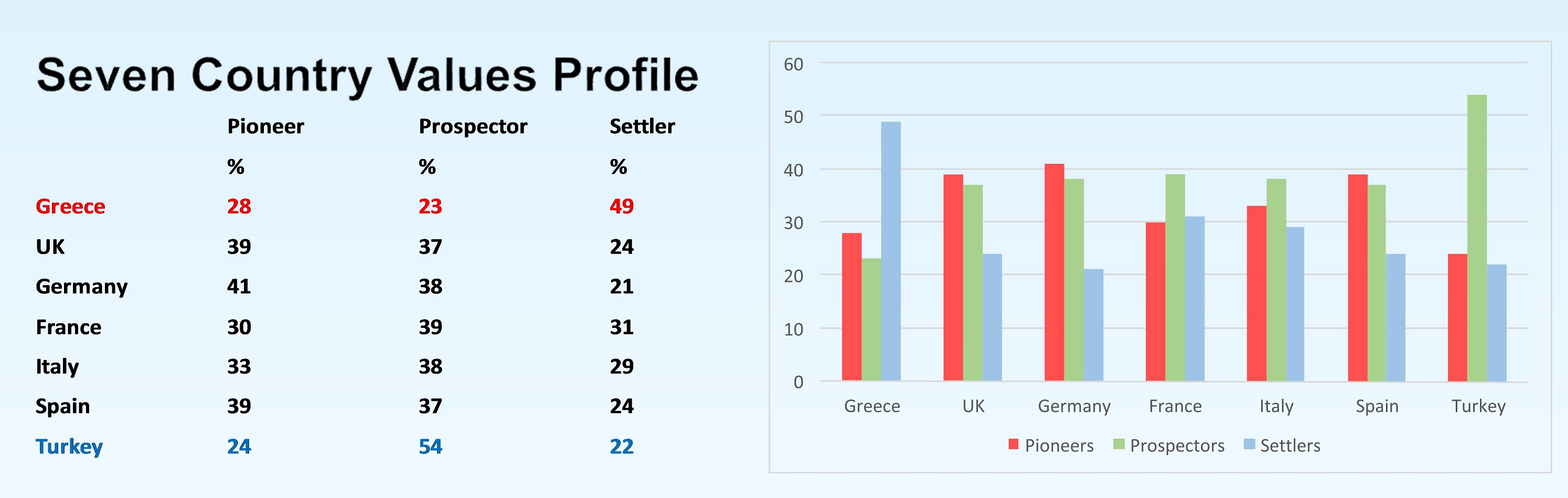

First, a values profile of Greece to lay a bench mark for the comments which follow. Here, the

values profile for Greece is shown in comparison with five other EU countries plus it's EU-aspirant

neighbour, Turkey.

Greece looks markedly different from both main European countries and from its close neighbour. The likely causes are explored below.

Our Greek data was gathered in the last 12 months – in other words, after the failure of the new Syriza government to significantly reconfigure its financial arrangements with the EU, particularly Germany. Previous governments had brought the country to the brink of bankruptcy and the ‘establishment’ parties had suffered badly as a result.

One of the questions the documentary posed repeatedly was how behaviours and attitudes in Greece could be compared to those in other EU democracies.

In terms of ‘economics’ and the handling of the economy - often used to compare countries - there was an obvious answer. ‘Greek politicians were corrupt and the body politic was misinformed or ill-informed about what was happening in the period between 2000 and 2010’. In other words, some people were greedy and/or short sighted; while others were complacent about the new, comfortable world opened to them by membership of the EU to the extent that they did not question the source of that comfort. But we know that ‘economics’ provides a very limited language to discuss the causes and effects of economic activity. Human activity, which drives economics, provides a better template for understanding issues that are essentially psychological and sociological.

Comparing which values are competing for dominance in the social narrative is a useful tool for understanding why some societies are likely to experience economic ‘surprises’ and why some are more resilient than others. Some seem to get right back up after a knockdown while others are slower to recover - or to react with counter-productive anger until circumstances change.

One of the factors in these behaviour sets is something that sociologists call the ‘low information group’ – a group of people who neither value nor access many sources of information about factors affecting their lives. Low information groups tend to be surprised by legislative or cultural factors that affect their work or set routines; by economic circumstances that rapidly change (for better or worse); and/or by changes in technology that can be foreseen by others but come as a surprise to them. By definition they lead circumscribed lives largely bypassed by the ‘information revolution’ so beloved of policy wonks and cultural commentators. These people tend not to be inclined to make a habit of looking for new thoughts and behaviours - preferring their familiar patterns of thought and behaviour, their own small world.

This ‘small world’ or ‘small life’ approach is inherent in the Settler values system.

Young Settlers may have a small life inclination because they have little life experience. But non-Settler young people have wider horizons, so simply being young is not a primary cause of having a small life. It is low information – especially new information – which is a prime determinant of a small life.

A ‘low information’ orientation to life may be due to sheer lack of access to the wider world – typically this is found in areas with little to no outside media. Over the last 100 years or so this has meant first radio then TV access. In the 21st century it is mobile phone connectivity and/or access to broadband.

In areas of low connectivity it is more likely the young will be connected and the old will not.

This creates conditions where younger and older Settlers may well have different reactions to changes in the world around them – or as we so often say to our clients ‘same motivation, different behaviours’.

In younger Settlers – especially those in cultures where Prospectors comprise a significant proportion of the population – their ‘small world’ approach often leads them to biased, special interest platforms for the ‘low information’ they access. They prefer sources that confirm their ‘low information’ point of view and are not particularly interested in alternatives. Among younger Settlers this tends to create ‘groups of interest’ in geographical areas that feel ‘distanced’ from other geographical areas. It also tends to lead them to the same web sites and social media sites over and over again – reinforcing opinions already held.

With the older Settler there is a stoicism, a resigned acceptance of unpleasant surprises in the past and an expectation of them in the future. Their ‘low information’ orientation is often driven by a sense of apathy and pessimism that comes from their low expectations being realized - “I didn’t expect much, and that is what I got.”

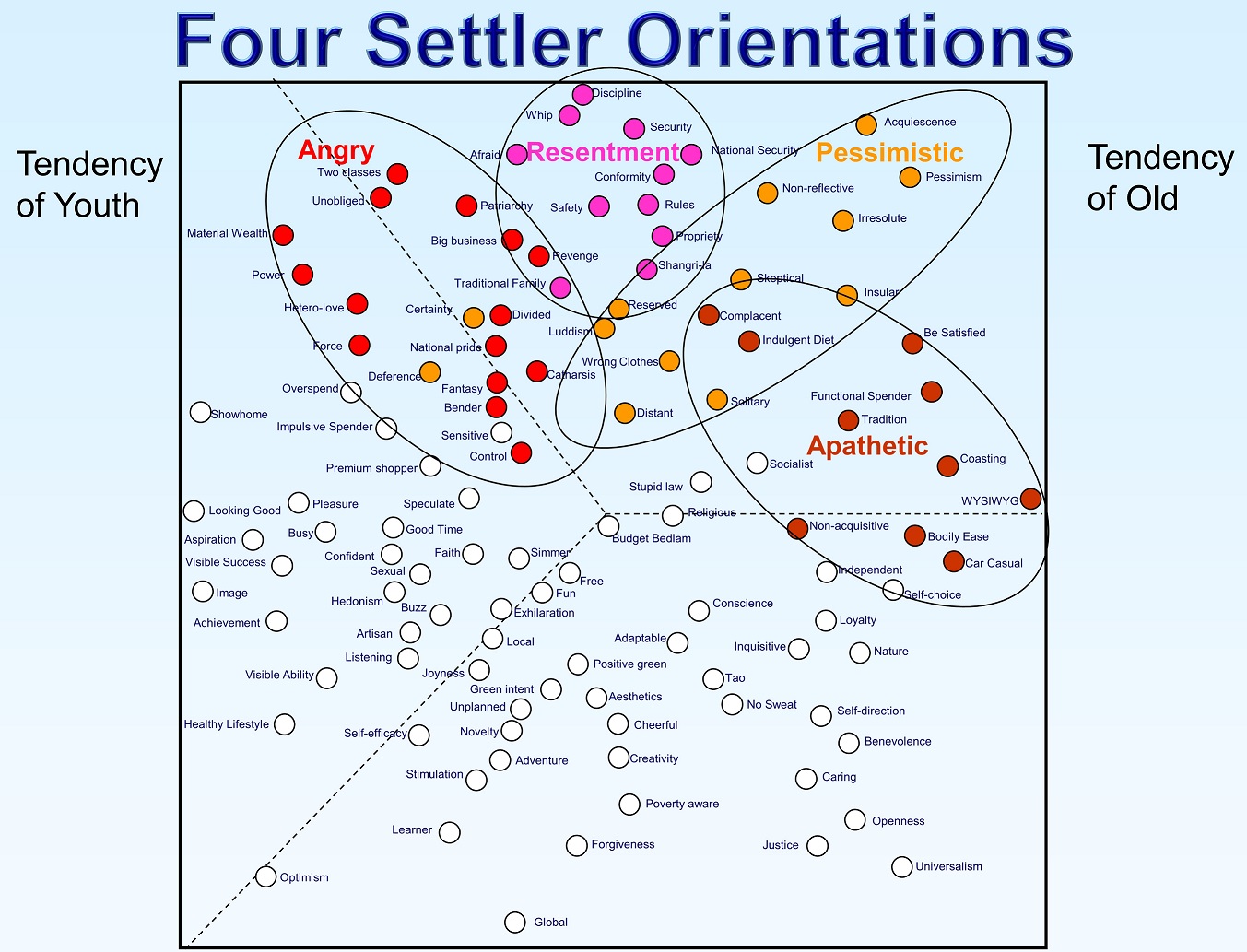

These differences within the Settler values set can be diagrammed in the following way:

Almost every attitude expressed in every scene in the documentary can be understood by understanding the Settler values set - the pessimistic tour boat operator who doesn’t want refugees coming through his home but understands their reasons for leaving their homes; the sponge fisherman who lives on his boat to eke out a living in a dying industry under highly dangerous conditions; the angry men holding onto a hatred for Germany and Germans because of Nazi genocide over 70 years ago; the angry unemployed youth throwing petrol bombs on the streets of central Athens – all are Settlers living Settler values.

These behaviours and attitudes also become easier to understand when the dynamics of values change are factored in. To measure a dynamic system more than one data point is needed – and the more data points, the more likely patterns are to emerge. In Greece we only have one data point, so we’ll use a model of change based on other, more data rich sources to understand what is being measured.

Several aspects of the CDSM values model show that:

- Individuals and cultures start with Setter values as their dominant values set.

- Once these values are satisfied, a change begins with a need to satisfy another set of values.

- Individuals and cultures can move from Settler to Prospector and then Prospector to Pioneer. Settlers cannot move to Pioneer without being Prospectors.

- Prospectors can move back to Settler values. Pioneers cannot return to either Prospector or Settler.

- If the attempt to satisfy values is thwarted or remains unfulfilled it is likely a retrenchment will be made back to the previous values set: so Prospectors will move back and become Settlers – the angry and resentful kind – while angry, resentful Settlers will move back to being pessimistic and apathetic Settlers.

As we’ve shown, Greece has a very different mix of values systems compared to other EU countries, so - in the most

basic of terms - the Greek populace will react differently from people in other EU countries, given the same situation.

With only one data point it is difficult to nail down the specifics of Greek values prior to 2015. What is known is that in the 15 or so years since joining the EU – roughly 2000 to 2015 - Greece had experienced an explosion of economic development with accompanying financial and political corruption on a significant scale.

Was Greece always corrupt - but just had less money to be corrupt with? Were Greeks always predominantly Settlers – but

more or less content with their ‘small life’? Did they want to become ‘European’ and make a healthy adjustment to their

new partnership? Or did they just want to remain Greek – but with perks? Have Greeks fundamentally changed? And if so,

from what to what? Or even from what to what to what?

While Greece doesn’t look European it doesn’t look like its near neighbour Turkey either. Anyone who has been to Greece or the islands will be struck by how much of life there is more Middle Eastern in look and feel than ‘European’.

CDSM data shows Turkey has a very similar values system to other ‘developing economies’. These countries are typified by about equal, and relatively low, numbers of Pioneers and Settlers and a significant majority - over 50% - holding Prospector values.

None of these developing countries has had the Greek experience of financial and social expectation being thwarted to the same extent.

Many of these developing countries have endemic financial and political corruption; but none we have measured have likely had Settler values satisfied and then had their emerging Prospector values stymied so quickly – with all these ‘surprises’ occurring within an advanced democratic framework of governance.

Given what we know about values shifts on individual and cultural levels we believe that over the last quarter of a century Greece began to emerge from Settler values modes. The stepping up of financial and legislative changes beginning in 2000 (including the Olympics and the World Cup) accelerated the changes in personal values and by extension cultural values to more Prospector values. In historical terms this could, ironically, be seen as little more than a decadent Roman Emperor’s practice of providing ‘bread and circuses’ to keep the populus quiescent.

These emergent Prospector values were fragile on the personal level and did not have the deep roots in cultural thinking and behaviours to safely anchor them when the collapse of the economic system occurred. When values are not satisfied they can go back to the last stage satisfied– and they very likely did in Greece.

Our Values snapshot is the result of the reversal of Greece’s fortunes and the loss of expectation of satisfying the Prospector values.

This understanding clarifies why Simon Reeve, the documentary presenter, felt that Greece didn’t feel like Europe. And our extrapolation from this recent values snapshot explains why it never did feel like Europe – it always felt Greek. And the ‘Greek’ felt by many northern Europeans travelling there over the last 25 years is likely to have felt more Prospector than their own countries, with the older people more Settler.

The retrenchment of values – the ‘shattered dreams’ phenomenon – is relatively new in Greece and is likely to spell longer term trouble to the financial and social structures devised by the original members of the then-EEC. These structures brought relative degrees of harmony to nations that tended to have a similar mix of values and dysfunctional histories of co-existence in the early to middle 20th Century.

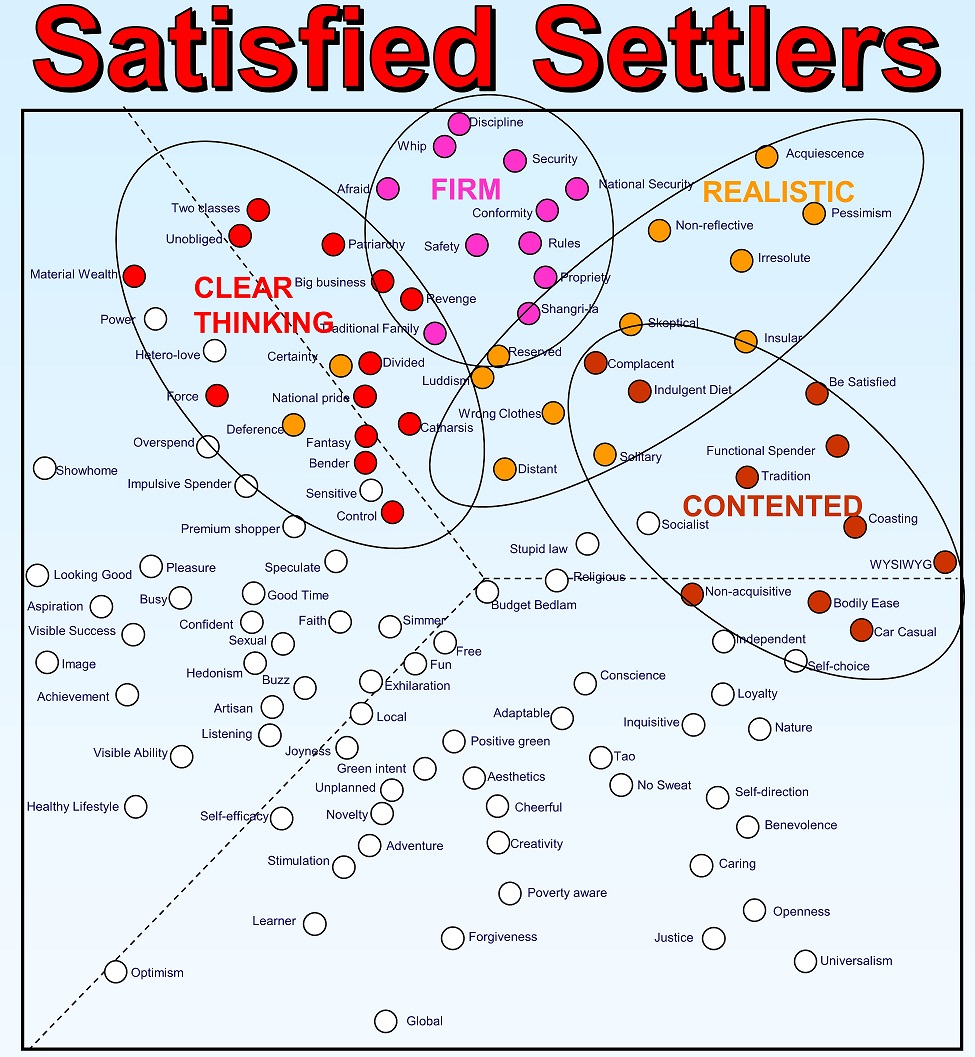

For Greece to regain the trajectory of gradually adopting Prospector values of ‘living the dream’, the apathy and pessimism of Settlers would have to be rejected for more clear thinking/realistic expectations – that, once satisfied, can become hopes and aspirations for something better. The new Settler map of Values would need to look more like this.

Settlers, by their nature, are more likely to follow leaders, good and bad, but they believe that pulling together as one people is better than everyone having great individual ideas. For them, democracy works best if they have belief in a strong leader. If the leader is a good Settler leader, they can get people to sacrifice in the short term for long term stability. They don’t need to promise bread and circuses today – just the promise of a world that is better for their children. The bad leader will provide bread and circuses and hope no one finds out it was paid for with debt and that the future is dark for the children.

People and cultures that are essentially Settler and emergent Prospector will tend to be ‘low information’ people and cultures. In their bread and circuses world ‘today’ is so comfortable – and better than yesterday – that there is little desire to expand their small life. The inevitable surprise is caused by a combination of psychological transition and bad, inept or corrupt leaders and institutions.

In their internal world of values, respect for the rule of law cannot be transgressed without consequences to the growth of the whole culture. This is the firmness that is required before clear thinking can occur. Signing treaties, assuming debt, changing institutions through legislation to finance debt, to facilitate structured growth is all a basic prerequisite to sustainable psycho-social development and economies that can thrive for the benefit of citizens.

Failure to recognize this dynamic has led to the outcomes outlined in the documentary – but also points the way to solutions which will change the situation for the better.

Without this understanding it is only a matter of time before angry, bitter unemployed Settler youths with shattered dreams leave behind their ritual confrontations with authority in the heart of Athens and take their Molotov cocktails elsewhere - into clearly identifiable affluent areas. They will likely ‘organise’ through the web and social media and their aim will be to disrupt the comfortable life enjoyed by those at the top of this most economically unequal of societies within Europe. If mass demonstrations, or small acts of violence, do not work in their broken democracy these angry young Settlers will try to ‘fix it’ in another way – this is what history tells us. This is where revolution begins.